How can we communicate better about methane and its climate risks? This project was trying to find the social and material levers that could help ground the otherwise abstract problem of invisible gases heating our planet. As an anchor, it focused on the city’s streets: their buried pipes, their above-ground trees, and the role they play in the history of the city.

Streets are the large contiguous public space that plays host to these two systems of public infrastructure and their interactions: the street trees of the urban forest, and the underground gas and utility infrastructure.

It turns out that the materials of the pipes in the underground gas system have a lot to do with the leak rate of methane from the system: Cast iron pipes are the leakiest, with potential for leaks at each of the old cast iron joints; coated steel pipe is newer and better, while the safest material is the new plastic replacement pipe. The gas utilities in the city have been slowly upgrading the system, replacing cast iron pipe with newer steel and plastic.

The language of gas infrastructure underfoot is legible if one happens to know the language. These spray-painted marks, refreshed whenever road work is imminent to avoid mistaken gas line ruptures, appear throughout the city. Working with Bob Ackley of Gas Safety USA, this project identified the basic semiotics of gas markouts.

Gas utilities in the city have been slowly upgrading the system, replacing cast iron pipe with newer steel and plastic. But until they manage to replace all the old pipe, the gas utilities have been doing repairs on individual leaks, in a city-wide game of whack-a-mole.

Comparing historic photos of the old city’s systems to the telltale signs of gas infrastructure on today’s streets, we can see that many of the old pipes are still there, some of them the original 100-plus year old cast (C.I.) iron. Repair patches located at 12-foot intervals (the spacing of joints in old cast iron pipe) is a tell-tale sign of an old cast iron main, repaired in place but likely springing new leaks faster than they can be sealed.

On Newbury Street, Boston’s iconic shopping street, the methane concentrations were among the highest in the city; dead and missing street trees lined up perfectly with measured persistent spikes in methane. Methane interacting with trees at the scale of the root tip (the tree-soil interface) slowly kills trees; methane interacting with the atmosphere (dissipating from belowground) acts as a powerful greenhouse gas, contributing to climate change.

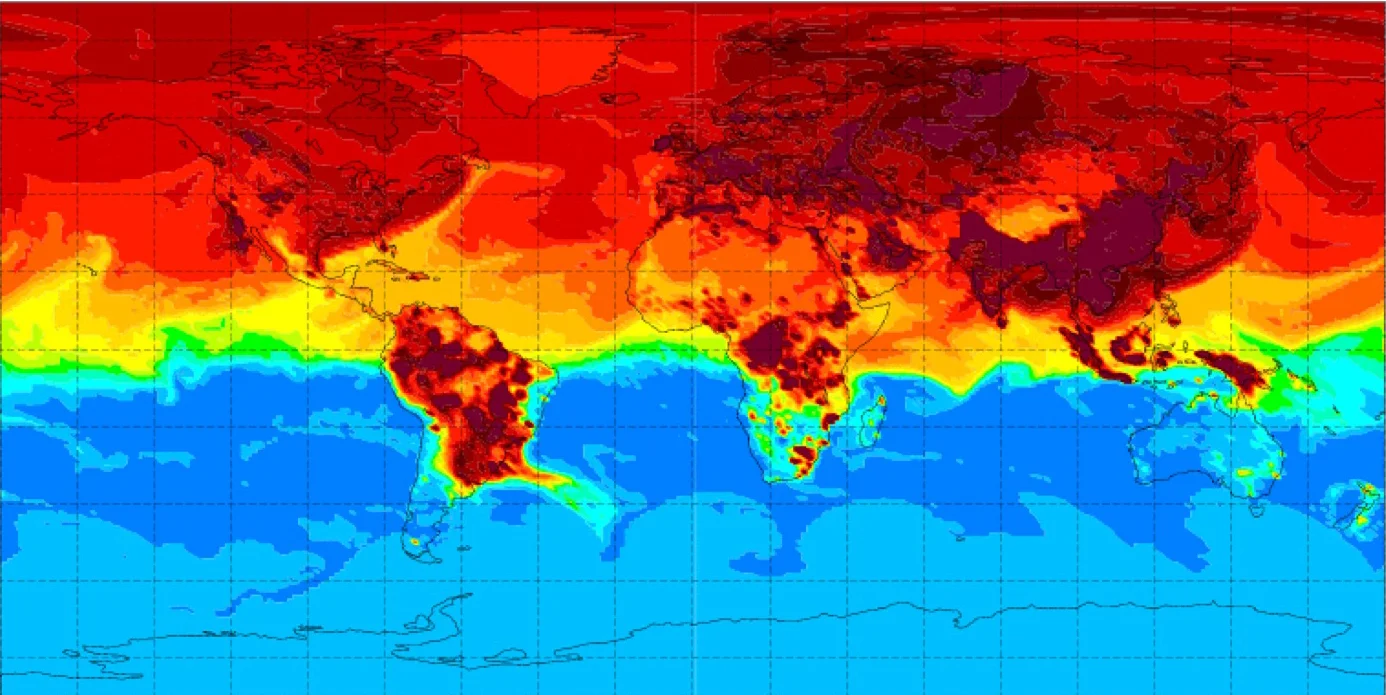

Aside from just visualizing the leaking methane and its climate-warming impact on Boston’s most iconic streets, this project explored how a focus on environmental justice communities, disproportionately at risk from heat stress in a warming world, might lead to new kinds of urban landscapes. How could a mission of addressing heat stress in EJ communities through the addition of urban tree canopy be combined with the pressing project of replacing leaky gas mains? What if EJ communities along an expanded Emerald Necklace could receive priority for gas pipe replacement, followed by aggressive afforestation in these climate-proofed neighborhoods? With the threat to trees from ongoing gas damage and digging having been eliminated, this aggressive afforestation would represent a much better public investment, leading to tangible improvements in streetscape and urban cooling. New iconic planting could serve to visually identify these streets as good climate citizens, which have made positive impacts on greenhouse gas mitigation.

Further Reading:

Other cities with old gas infrastructures have similarly wrestled with the leaky legacy of gas, amid new visions for urban transformation. Read about New York City’s experience with leaking methane here, from the scale of the street to the scale of the region:

https://urbanomnibus.net/2018/09/gas-flows-below/